Inside Water: Stories of Water Polo Around the Globe

The Collegiate Water Polo Association launched a periodic series of articles on interesting, peculiar and otherwise out of the ordinary facts, figures and personalities from the sport of water polo on August 1, 2009 called “Inside Water”. The only series of its kind in the sport, the articles are meant to bring to light people, places and events which had an impact on the game, either directly or indirectly, and how these factors have changed life as we know it.

- Hanson Baldwin

- Edwin Hubble

- Sheldon Leonard

- Jimmie Johnson

- Dr. William Brody

- Jam Handy

- Dr. Theodore Schlegel

Inside Water: The Life & Times of Journalist Hanson Baldwin

BRIDGEPORT, Pa. — Although water polo is a relatively new National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) sport, the history of the game goes back nearly 100 years with players abounding from the founding days of the sport who went onto achieve success both in and out of the water.

Earlier this year, we featured television Hall-of-Fame member Sheldon Leonard of Syracuse University. Now we turn our attention to the Military Academies.

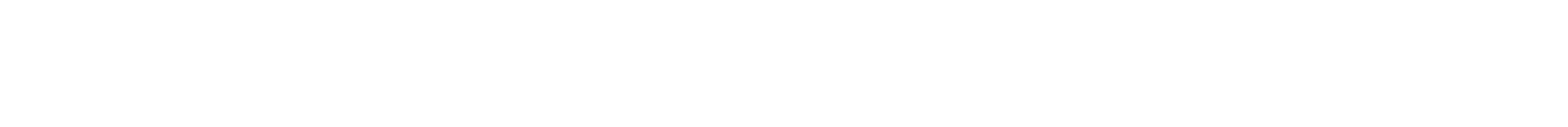

Among the early notable players of the game was Hanson Weightman Baldwin, a 1924 graduate of the United States Naval Academy who went on to make his name in news as the long-time military editor for the New York Times and a military historian.

Born to The Baltimore Sun managing editor Oliver Perry and Caroline (Sutton) Baldwin in Baltimore, Maryland on March 22, 1903, he attended the Boys’ Latin School of Maryland in Baltimore and graduated from the United States Naval Academy in 1924 following a career as a water polo player for the Midshipmen.

After three years of naval service, most of it aboard a destroyer and a battleship, he resigned his commission and began his newspaper career in 1927 as a reporter for The Baltimore Sun. He joined the New York Times in 1928 and wrote for them for the next forty years. In 1937 he became the paper’s military analyst. That year, he spent four months in Europe reporting on the military preparedness for what was viewed as the coming war. One of his first major stories in 1938 was of the interception of the ocean liner Rex by U.S. B-17 Flying Fortresses, in which he personally participated.

During World War II he wrote from the South Pacific, North Africa and Europe. His dispatches from Guadalcanal and the Western Pacific won him the Pullitzer Prize in 1943. In 1959 he broke the news of high-altitude atomic bomb test by the United States, known as Project Argus. In August 1962, his report on the Soviet Union fortifying its nuclear sites inside concrete bunkers brought about a wire-tapping of his phone and office by the Central Intelligence Agency on the orders of President John F. Kennedy, marking the first time on the record that a president used the CIA to spy on the press.

Besides working for The Times, he lectured and wrote regularly for magazines, scholarly quarterlies and for professional military publications. His papers were given as “The Hanson W. Baldwin Collection” to the George C. Marshall Research Foundation.

He was one of the nation’s leading authorities on military and naval affairs during the postwar transition from conventional warfare to the nuclear age. A tall, slender, courtly man, Mr. Baldwin had a quiet manner that belied his forceful opinions.

In addition to the European and Pacific battles of World War II, Mr. Baldwin covered the strategy, tactics and weapons of war in Korea, Vietnam, the Middle East and other theaters before retiring from The Times in 1968.

His articles, many marked “military analysis,” were often more than reportorial, blending his own opinions and those of the nation’s military chiefs into the news of specific military situations, so that what emerged was a broader view of strategic considerations and their national and international political implications. Advocate of Nuclear Superiority

Mr. Baldwin was often aligned with Pentagon military chiefs on major strategic issues and budgetary matters. He frequently opposed the “gradualism” of political leaders whose restraints, he felt, stood in the way of battlefield victories or military superiority for the United States.

He contended that the United States was engaged in a “struggle for the world” with an aggressively expansionist Communism, and he was an outspoken advocate of nuclear superiority over the Soviet Union.

At various times, he also advocated the intensification of the Vietnam War to achieve a military victory, and friendship with Spain under Franco and with white-dominated Governments in South Africa and in Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, because of what he regarded as their strategic positions.

Generals, admirals, Presidents and members of Congress read his articles, sometimes with respect and sometimes with exasperation. His views occasionally became the focus of news, as they did in 1966 when Defense Secretary Robert S. McNamara called a news conference to dispute his contention that the Vietnam War had overextended the armed forces.

The Times itself occasionally disagreed with his opinions. In 1965, for example, he argued in an article in The New York Times Magazine for a stepped-up American military commitment in Vietnam, including one million soldiers and saturation bombing of North Vietnam, to stop the “Communist strategy of creeping aggression” before it swallowed up all of Asia.

In an editorial, The Times said such a policy would be “a surer road to global holocaust than to a ‘victory’ arms can never win for either side.”

Mr. Baldwin’s opinions sometimes drew the wrath of the Soviet Union. Pravda once referred to him as a “cannibal in an American tunic,” and Krokodil, a Soviet satirical magazine, published a cartoon depicting him as a fat little man in an admiral’s hat seated in a puddle of ink and surveying the world through the wrong end of a telescope.

After his retirement, Mr. Baldwin continued to write articles on military affairs for the news columns of The Times and its Op-Ed page. He also continued to write books and many magazine articles on strategic issues and intelligence matters, and served as president of the Naval Academy Alumni Association.

After his retirement from the New York Times in 1968, Hanson Baldwin became an editor at Reader’s Digest and continued to write Op-Ed pieces in the Times. He retired from the Digest in 1976.

He authored scores of books on military and defense topics. His books published are: Men and Ships of Steel (1935), We Saw It Happen (1938), The Caissons Roll (1938), Admiral Dealth (1939), What the Citizen Should Know About the Navy (1941), United We Stand (1941), Strategy for Victory (1942), The Navy at War (1943), The Price of Power (1947), Great Mistakes of the War (1949), Sea Fights and Shipwrecks (1955), The Great Arms Race (1958), World War I: An Outline History (1962), The New Navy (1964), Battles Lost and Won: Great Campaigns of World War II (1966), Strategy for Tomorrow (1970), The Crucial Years, 1939-1941 (1976), and Tiger Jack (1979).

Besides the Pulitzer Prize, he received many awards and prizes, including the Distinguished Service Medal from Syracuse University in 1944. He also received honorary degrees from Drake University and the Clarkson Institute of Technology.

In 1972, he was one of the first individuals honored with the NCAA Prominent National Media Salute, an award honoring outstanding former athletes who achieved success and reknown in the field of journalism. Joining Baldwin on the list of honorees were Frank Gifford, Curt Gowdy, Howard K. Smith, Chet Forte and Arthur “Bud” Collins, among others.

Away from the pool and the typewriter, he married Helen Bruce Baldwin (1907-1994) of Urbana, Ohio in 1931 who made a name for herself as a poet and author of articles on culinary subjects for various magazines. They had two children; Barbara Potter and Elizabeth Crabtree. The Baldwins lived in Chappaqua, New York. In 1947, Rabbi Michael Dov Weissmandl bought the Brewster estate in nearby Mount Kisco and moved the Nitra Yeshiva there to create a self-sustaining agricultural community known as the “Yeshiva Farm Settlement”. At first this settlement wasn’t welcomed by its neighbors, but in a town hall meeting, Mrs. Baldwin, impressed by Rabbi Weissmandl, defended its establishment and wrote a letter-to-the-editor to the New York Times regarding it. She eventually was instrumental in even getting its neighbors to donate to the Yeshiva. In this settlement which is now called the Nitra Community, she is fondly remembered for her valor and kindheartedness.

Baldwin died in Roxbury, Connecticut on November 13, 1991.

Inside Water: The Life of Edwin Hubble

Dec 20, 2009

BRIDGEPORT, Pa. — Not all water polo players have made their name in the water, nor have all players gone onto make a name which transcended the terrestrial plane.

But for one player from the Heartland of America, his work and name have transcended the realm of science and Earth to stand apart for explaining that the Milky Way Galaxy is but one of an ever-growing number in the universe.

Born to Virginia Lee James, from Virginia City, Nevada, and John Powell Hubble, an insurance executive from Missouri, in Marshfield, Missouri on November 20, 1889 during a visit to his father’s parents, Edwin Powell Hubble‘s family moved to Wheaton, Illinois, in 1898 to be closer to his father’s offices in Chicago.

Renowned more for his athletic abilities as a child, including seven first and a third place finish at a high school track meet in 1906, Hubble achieved both athletic and academic success. Excelling in every subject except spelling, the Illinois state high jump record-holder for a number of years took an interest in fly-fishing and amateur boxing in his youth in addition to novels, including those of Jules Verne.

On his high school commencement day in 1906, the principal said, “Edwin Hubble, I have watched for four years and I have never seen you study for ten minutes.” He then paused and continued, “Here is a scholarship to the University of Chicago.”

However, by mistake, his high school scholarship was also awarded to another student, thus the money had to be halved, and Hubble had to supply the rest. He paid his expenses by tutoring and summer work, before earning a scholarship in physics and by working as a laboratory assistant to Robert Millikan in his junior year.

Excelling in mathematics, astronomy, and philosophy to earn a Bachelor of Science degree in 1910, he also performed well in athletics earning letters in track, boxing and basketball.

A member of the Kappa Sigma Fraternity at Chicago, and the organization’s 1948 Kappa Sigma “Man of the Year”, he spent the next four years after earning his bachelor’s degree in England at Oxford University’s Queens College as one of the first Rhodes Scholars.

It is at Oxford where he picked up the sport of water polo, competing for the university’s team while continuing his academic studies. Originally a jurisprudence major, he changed his major to Spanish in which he earned a master’s degree before returning to the United State in 1913.

Upon returning to North America, he acquired a position as a teacher of Spanish, physics, and mathematics at the New Albany High School in New Albany, Indiana. He also coached the boys’ basketball team there in addition to earning admission as a member of the Kentucky bar association, practicing law for a year thereafter in Louisville.

He reported that at this time he “chucked the law for astronomy, and I knew that even if I were second-rate or third-rate, it was astronomy that mattered.” Thus in 1914 he returned to the University of Chicago’s Yerkes Observatory for postgraduate work leading to his doctoral degree in astronomy.

While finishing work for his doctorate early in 1917, Hubble was invited to join the staff of the Carnegie Institution’s Mount Wilson Observatory, Pasadena, California, by founder George Ellery Hale. Although this was one of the greatest of astronomical opportunities, it came in April with World War I raging on. After sitting up all night to finish his Ph.D. thesis, and taking the oral examination the next morning, Hubble enlisted in the infantry and telegraphed the Observatory, “Regret cannot accept your invitation. Am off to the war.”

He was commissioned a captain in the 343d Infantry, 86th Division and later became a major. He was sent to France where he served as a field and line officer. He returned to the United States in the summer of 1919, was mustered out in San Francisco, and went immediately to Pasadena’s Mount Wilson Observatory where he remained with a few interruptions for the remainder of his life.

It is at Mount Wilson over the next 22 years that he changed the world’s perspective of the universe as he photographed the sky through the Hooker Telescope, then the most powerful telescope in the world. Hubble identified Cepheid stars within the Andromeda Nebula, and proved that they were outside of the Milky Way galaxy, as part of identifying other galaxies to affirm for the first time that our galaxy is one of millions within the universe. Hubble also used the Hooker telescope to develop “Hubble’s Constant,” which defines the linear relationship between a galaxy’s distance and the speed with which it moves. Hubble noted that the farther apart galaxies are from each other, the faster they move apart, illustrating that the Universe is expanding uniformly. This conclusion helps to substantiate the “Big Bang” theory, which states that everything in the universe originated from a single point and dispersed from there.

In addition to his research, Hubble settled down and married Grace Burke on February 26, 1924, before the outbreak of World War II led to his relocation to the U.S. Army’s Aberdeen Proving Grounds in Maryland. For his work there he received the Medal of Merit award in 1946 for “outstanding contribution and achievement in ballistics research.”

After the end of World War II, he returned to Mount Wilson to contribute to the design of the Hale telescope and helped direct the building of the Palomar Observatory, where he worked until his death from a cerebral thrombosis (a spontaneous blood clot in his brain) on September 28, 1953 in San Marino, California. No funeral was held for him, and his wife never revealed what happened to his body, taking the secret to her grave. Today, one of NASA’s most advanced tools, the Hubble Telescope, serves as a legacy to the great astronomer. The Hubble mission began in 1990 when the telescope was launched to orbit the Earth outside of the atmosphere. It has since provided hundreds of thousands of images and helped researchers determine the age of the universe.

Ironically, the telescope that bears his name was revived in 1997 by another water polo player, as seven-time swimming and water polo All-America Steve Smith, who led the Stanford University Cardinal to two NCAA water polo championships, was the primary astronaut repair technician.

Inside Water: Water Polo on the Big Screen – The Story of Sheldon Leonard

Aug 03, 2009

BRIDGEPORT, Pa. – When the “Inside Water” series was envisioned while standing in the pouring rain at the 2009 Women’s National Collegiate Club Championship at the University of California-Davis (and yes, it does rain in “Sunny California”), it was intended to bring to light little known or odd facts in the history and game of water polo which have either never rarely been highlighted or forgotten in the midst of a sports world dedicated to the “Big Four” (football, basketball, baseball, hockey).

Fittingly, the inaugural subject of the series is known by name to some, by his face to others and to all by his impact on the preeminent vehicles of American pop culture over the last 75-years – film, radio and television.

Born Sheldon Leonard Bershad in New York City on February 22, 1907 to middle class Jewish parents Anna and Frank Bershad, the Museum of Broadcast Communications notes that for “nearly two decades, from the early 1950s through the late 1960s, Sheldon Leonard was one of Hollywood’s most successful hyphenates, producing–and often directing and writing–a distinctive array of situation comedies, of which three justly can be considered classics (The Danny Thomas Show, The Andy Griffith Show, The Dick Van Dyke Show). Although he assayed the hour-long espionage form with conspicuous success as well, the sitcoms remain the Leonard hallmark. Long before Taxi and Cheers, Leonard was overseeing the creation of literate, character-driven ensemble comedies that blended the domestic arena with the extended families of the modern workplace.”

But what connection does a TV producer, director, occasional actor and father of the television medium have to the sport of water polo? Funny you should ask that question on a site dedicated to collegiate water polo, especially on the East Coast.

Following his formative years in Belleville and later lower Manhattan, he attended Stuyvesant High School and was the right guard on the 1925 Municipal Championship football team, and advanced on to Syracuse University where he studied theater and was a varsity athlete on the swimming/diving and water polo teams.

Following graduation, he moved into the role of head counselor of Camp Wakitan in the Ramapo Mountains of upstate New York before planning a career as a stockbroker on Wall Street.

History has a funny way of changing plans, however, as his first day as a junior broker for Bauerdorf and Company occurred on October 24, 1929. On that date, the market shed 33 points – a drop of 9 percent- to begin the Great Stock Market Crash of 1929 with the subsequent impact of the Great Depression occurring for the next 12 years to the beginning of World War II.

Out of work two weeks after beginning his new job, Leonard worked odd jobs until being tipped off to the Paramount Theatre Company’s program for assistant theatre managers. Following completion of the course, he was sent to the Eastman Theatre in Rochester, New York – a fortuitous event which launched his stage and screen (both big and little) careers.

Following a few years working behind the scenes, he took a position on the stage in the early 1930’s. After six years acting on Broadway–during which time he also took his first stab at directing, for road companies and summer theater–in 1939 Leonard made the move to Hollywood, where he would go on to appear in fifty-seven features over the next fourteen years including notable cinematic events as to Have and Have Not, It’s a Wonderful Life, Another Thin Man, Decoy, Abbott and Costello Meet the Invisible Man, Sinbad the Sailor, Guys and Dolls and Pocketful of Miracles (with Frank Sinatra).

Besides his cinematic appearances, he was keeping busy on the radio with regular roles on several programs (The Jack Benny Show, The Lineup and Duffy’s Tavern, to name only a few), and guest parts on dozens of others. Although Leonard played a number of roles on both the silver screen and radio, he is best remembered for his incarnations of quietly-menacing gangsters due to his Brooklyn-toned voice.

One of his most notable roles was portraying an eccentric racetrack fan known as the “Tout” on The Jack Benny Program in the late 1940’s and early 50’s. His role was to salute Benny in different locations with the same quote “hey Bud, come here a minute”, ask what Benny was going to do, try to argue him out of that course of action using irrelevant racing logic. He also appeared on “The Adventures of the Saint”, most often playing thugs or gangsters, but sometimes in more positive roles.

As the 1940’s wore on, he kept acting and took up writing for radio programs selling scripts for anthology shows, all of which he retained the rights to for future potential sales. In addition, he tried his hand at directing while learning the inner workings of the writing and producing fields.

After a while, the advent of television brought about a new slew of opportunities as he turned to writing for the new media outlet.

Moving away from radio, Leonard signed on as director of the Danny Thomas series Make Room for Daddy in 1953. He was promoted to producer in the show’s third year, remaining its resident producer-director for six more seasons. Between 1954 and 1957 he also found time to produce and direct the pilot and early episodes of Lassie and The Real McCoys (which was produced by Thomas’ company), write and direct installments of Damon Runyon Theatre–as well as act in a 1954 summer replacement series, The Duke. In 1961 Leonard became Executive Producer of the Thomas series (titled The Danny Thomas Show), at which time he and the comedian teamed up to form their own production firm.

T and L Productions would go on to make a lasting mark on television comedy. At its peak in 1963, T and L had four situation comedies in prime time, with Leonard serving as Executive Producer on all four: The Danny Thomas Show, The Dick Van Dyke Show, The Andy Griffith Show, and The Bill Dana Show. Through their own separate companies Leonard and Thomas also owned an interest in a fifth sitcom, The Joey Bishop Show, although Leonard had no creative role in the series after directing the pilot. To complete the T and L comedy empire, the partners each owned an interest in My Favorite Martian by virtue of Thomas’ financing and Leonard’s direction of the pilot, and also owned The Real McCoys syndication package. Although the Bishop and Dana programs were short-lived, Danny Thomas, Dick Van Dyke, and Andy Griffith were all certifiable Top Ten Nielsen hits.

Consider some of the characters and actors which were on these shows. Most notably, consider The Andy Griffith Show launched the career of not only Griffith, but also Don Knotts and actor/director Ron Howard.

Further, it was Leonard who recognized the story and character quality in a failed pilot written by and starring Carl Reiner, and resurrected it by casting Dick Van Dyke in the lead role–retaining Reiner’s writing talents – for The Dick Van Dyke Show.

Behind the scenes, his impact was equally felt as he fostered and mentored the talent of writers, notably Danny Arnold (Barney Miller), and the teams of Garry Marshall and Jerry Belson (The Odd Couple, Happy Days, etc.), and Bill Persky and Sam Denoff (That Girl, Kate and Allie).

Although not the first to come-up with the idea of a spin-off (radio program Fibber McGee & Molly spun-off the Great Gildersleeve in the 1940’s), Leonard brought the idea to television to avoid the cost of making a pilot episode.

Both the Andy Griffith and Joey Bishop shows began with “back-door pilots” (directed by Leonard) aired as episodes of Danny Thomas; similarly, Bill Dana’s “José Jimenez” character began as a recurring character on the Thomas show before setting out on his own series. While the Dana and Bishop programs did not work out so well, another spinoff from The Andy Griffith Show did in 1964 when sent a popular resident of Mayberry off into six years of military misadventures on Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C.

Following the break-up of his partnership with Thomas in 1965, Leonard kept working and came up with the comedic spy series I Spy.

However, the most significant aspect of the series was Leonard’s decision to cast then not-widely known African-American comedian Bill Cosby opposite Robert Culp as the series leads to make Cosby the first African-American lead actor in network television history. The series was nominated for Outstanding Dramatic Series Emmy every year of its three-year run, earned Leonard an Emmy nomination for directing in 1965 and launched the career of actor Bernie Koppell, who went on to play Doc on Love Boat.

In addition to directing and producing, he continued to work as an actor recreating his radio role as the racetrack tout on Jack Benny, appearing as Danny Williams’ agent on Danny Thomas, and doing a gangster turn in a Dick Van Dyke episode. Still typecast after almost forty years, Leonard acted the tough guy yet again in 1975 as the star of the short-lived series Big Eddie (as a gambler-turned-sports arena owner), and once more in 1978 in the made-for-TV movie The Islander (as a mobster). That same year Leonard acted in the TV movie Top Secret, a tale of international espionage starring and co-produced by Bill Cosby. More recently, Cosby recruited Leonard to fill the Executive Producer slot on I Spy Returns, a 1993 TV-movie sequel that reunited Culp and Cosby as the secret agents.

He was also active in cartoons and adverting serving as the voice of lazy cat Dodsworth in two 1950’s Warner Bros. cartoons before providing the voice of Linus the Lionhearted in a series of Post Crispy Critters cereal commercials in 1963-64. He repeated his performance as Linus in a Saturday morning cartoon series which ran on CBS (1964-66) and ABC (1967-69). In addition, he shares the title of being the first Miller Lite spokesman with crime author Mickey Spillane.

In one of his final acting roles, he made an appearance on potentially the pinnacle series of the 1980-90 period, Cheers, on which he appeared as the proprietor of “The Hungry Heifer,” Norm Peterson’s favorite eating establishment.

The recipient of multiple awards, including three Emmys and a Golden Globe, he was honored by the NAACP for his role in breaking the “color barrier” with Cosby’s casting on I Spy and was inducted into the Television Hall of Fame in 1992. Even today, he continues to receive homages as the lead characters on the CBS Emmy-nominated show “The Big Bang Theory” are named Sheldon and Leonard in his honor.

Active on screen and in television production until his death on January 19, 1997 in Culver City, California at the age of 89, his position of success and impact on American culture following a time as a collegiate athlete was recognized by the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) in 1969 as he was the recipient of a Performing Arts Salute, one of only five water polo athletes recognized by the organization with a post-collegiate award/salute.

Actor, director, producer, innovator, water polo player. Not a bad career, and one that deserved a spotlight.

Thanks to the Museum of Broadcast Communications for assistance in this piece and Sheldon Leonard’s autobiography “And the Show Goes On”.

Inside Water: NASCAR Champion Jimmie Johnson & Water Polo

BRIDGEPORT, Pa. — Some of the great athletes and businessmen of the last 100-years have excelled in the sport of water polo. But only one is “Superman” – at least to his competitors and teammates – and a five-time champion to boot. Five-time National Stock Car Racing (NASCAR) Sprint Cup champion and 2009 Associated Press Athlete of the Year Jimmie Johnson makes his living driving fast, turning left and wowing the crowds on Sunday for money, but it was in El Cajon, California, Granite Hills High School and the water that the legend began in earnest.

The oldest of three, Johnson was born on September 17, 1975, in the San Diego suburb of El Cajon to a blue-collar family, Johnson’s mother, Cathy, drove a school bus and his father, Gary, operated heavy machinery. At the age of four, Johnson could handle a 50cc motorcycle. He was racing by age five and won his first championship at age eight, racing larger 60cc motorcycles. Johnson learned from some of the best and found an early mentor in motocross and supercross champion Rick Johnson (the two men are not related).

When Jimmie Johnson was seven, Rick Johnson attended one of his competitions and predicted a bright future for the pint-sized racer. During the race, Johnson approached a six-foot jump, sailed his bike 65 feet through the air and stuck the landing, though he later spun out into a crash. Rick Johnson was amazed watching Jimmie Johnson fearlessly attack the jump.

“That was when I knew he had the talent to go into the corner at 190 mph,” Rick Johnson told USA Today’s Nate Ryan.

As a teen, Johnson accompanied his dad to local off-road races. The excitement got under his skin and soon, Johnson was chatting with the buggy owners, trying to charm his way into a deal that would allow him to drive.

After being offered the chance, Johnson quickly impressed the crowds. He spent several years racing trucks, both off-road and in stadiums, winning his first championship at 17.

Racing was not his only sports passion. Before graduating from suburban San Diego’s Granite Hills High School in 1993, Johnson played water polo and competed with the swim team. Johnson’s truck-racing career was fraught with ups and downs. During the 1994 Baja 1000 endurance race, Johnson—after 20 hours of racing—fell asleep behind the wheel in the middle of the Mexican desert, flipping his vehicle into a sand wash. Johnson and his co-driver were rescued two days later. For days, Johnson stewed over the mistake.

From that day forward, Johnson strove to be a cleaner, more precise driver. Johnson left California in 1996, when he was 21, and headed to Charlotte, North Carolina, hoping to forge a connection with race team owners.

He was patient and persistent in his efforts.

“I would go to places where I knew crew guys ate lunch and I’d sit there all through lunch just trying to meet people,” Johnson told Sports Illustrated’s Lars Anderson.

Johnson’s persistence paid off and in 1997 he raced in the American Speed Association’s short-track series, though the switch to pavement racing took some getting used to. In his first race with the AMA, Johnson spun his car 12 times. He quickly mastered the discipline and in 1998 was named the series’ Rookie of the Year.

In 2000, Johnson graduated to the Busch (now Nationwide) series, NASCAR’s second-tier race series. That year, Johnson raced to six Top 10 finishes and ended tenth in points.

Johnson entered the NASCAR Cup series full-time in 2002, after being recruited to drive the No. 48 Lowe’s Chevrolet Monte Carlo co-owned by Rick Hendrick and race champion Jeff Gordon.

From the start, Johnson proved he was a contender and for a time in 2002 led in points standings—the first rookie to ever do so. Johnson proved to be a consistent driver but suffered many ups and downs. In 2004, he crashed twice in the first four of the Chase for the Championship final race series of the year. Johnson has a strict pre-race routine that begins with a team meeting to discuss strategy. Next, he sits in the team hauler alone, emptying his mind and focusing on the race. During this time, he visualizes hitting his marks on each lap. After introductions over the loudspeaker, he gets into the car and gets settled. Johnson tore up the tracks during his first four seasons in the Nextel Cup series, though patches of bad luck kept him from the title.

The 2006 season was no different. The season got off to a bumpy start when his crew chief, Chad Knaus, was fined and suspended for four races for making illegal modifications to Johnson’s car during qualifying runs for the season-opening Daytona 500. However, Johnson went on to win the race. During the season, he also won the Aaron’s 499 at Alabama’s Talladega Superspeedway and the Allstate 400 at the Brickyard. He finished first in points standings, finally capturing the elusive title and a $6.2 million check.

The titles have kept on coming since as he captured the Sprint Cup crown in 2007, 2008, 2009 and 2010 becoming the first driver in the history of the sport to claim five consecutive titles. Consider that in the history of the sport the all-time record for career titles is seven (held by Richard Petty and Dale Earnhardt). Less than a decade into his career, Johnson is nearly 72% of the way to equaling the feat. Since 2006, the 35-year-old has claimed 35 of his 53 career wins, claimed five straight titles, eclipsing the previous mark of three straight standard set by Cale Yarborough from 1976-79. Kyle Busch (17) has the second-highest wins total since 2006. Johnson leads the series with a 16.36-percent win percentage (Busch is second at 8.6 percent), 81 top-5s, 117 top-10s and 7,655 laps led. Further, consider that Petty needed 654 races to win five titles, although he ran as many as 60 races a season in some seasons. Earnhardt required 390 races. Johnson has done it in 327.

Nicknamed “Superman” by teammate Mark Martin a few years ago for all of his success, Johnson has made an even greater mark off the track. Away from the track, Johnson launched the Jimmie Johnson Foundation in February 2006. The Jimmie Johnson Foundation is dedicated to assisting children, families and communities in need throughout the United States. The Foundation strives to help everyone, particularly children, pursue their dreams. The Jimmie Johnson Foundation supports charitable organizations that further the mission of the foundation. Current and past projects include granting wishes for children through the Make-A-Wish Foundation, assisting the American Red Cross with disaster relief efforts, building a four-lane bowling alley for children with chronic and life-threatening illnesses at the Victory Junction Gang Camp in North Carolina and hosting a golf tournament in San Diego to raise funds to build a Habitat for Humanity home in Johnson’s home town of El Cajon.

So, when the season opening Daytona 500 rolls around and the tires start spinning, remember that the sport of water polo has a connection to the sport of racing’s best.

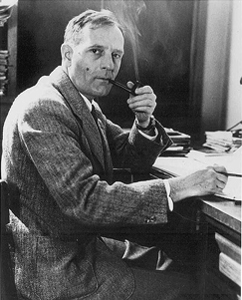

Inside Water: Former Johns Hopkins University/Salk Institute for Biological Studies President Dr. William Brody

BRIDGEPORT, Pa. — An acclaimed physician-scientist, entrepreneur and university leader, Dr. William R. Brody left the Massachusetts Institute of Technology following an undergraduate career in which he competed on the men’s water polo team to make his mark in the world as one of the preeminent academic and scientific leaders of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Appointed the head of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, Calif. on October 13, 2008, after 12 years as president of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Md., Dr. Brody is the focus of the latest “Inside Water” feature by the league’s communications staff.

Launched as a periodic series of articles on interesting, peculiar and otherwise out of the ordinary facts, figures and personalities from the sport of water polo on August 1, 2009, the “Inside Water” articles are the only series of their kind in the sport which aim to shine a spotlight on people, places and events which had an impact on the game, either directly or indirectly, and society.

Currently a Professor Emeritus at the Salk Institute and a native of Stockton, Calif., Dr. Brody received his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in electrical engineering from MIT following a standout academic career in the classroom and laboratory to accompany time in the water as a member of the men’s water polo team at the institution. He earned his doctorate (also in electrical engineering) and his medical degree (MD) from Stanford University. He continued his postgraduate training in cardiovascular surgery and radiology at Stanford, the National Institutes of Health and the University of California-San Francisco.

Between 1977 and 1986, he held appointments at the Stanford University School of Medicine, including professor of radiology and electrical engineering; director of the Advanced Imaging Techniques Laboratory; and director of Research Laboratories, Division of Diagnostic Radiology. In 1987, he moved to the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine where he held several appointments, including the Martin W. Donner Professor of Radiology; professor of electrical and computer engineering; professor of biomedical engineering; and radiologist-in-chief of The Johns Hopkins Hospital. After a two-year stint as provost of the Academic Health Center at the University of Minnesota, he was named president of Johns Hopkins University in 1996 and served until taking over as President of the Salk Institute from 2008 until his retirement in 2015.

During his seven-year tenure as The Salk Institute for Biological Studies, an independent nonprofit organization dedicated to fundamental discoveries in the life sciences, the improvement of human health and the training of future generations of researchers, Dr. Brody oversaw Salk’s 870 scientific staff, including three Nobel Prize recipients, and directed the Institute’s research objectives.

Named for Jonas Salk, M.D., whose polio vaccine all but eradicated the crippling disease poliomyelitis in 1955, The Salk Institute was founded by its namesake in 1960 with a gift of land from the City of San Diego and the financial support of the March of Dimes. The Salk Institute currently focuses its research in three areas: molecular biology and genetics; neurosciences; and plant biology. Research topics include cancer, diabetes, birth defects, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, AIDS, and the neurobiology of American Sign Language. The institute consistently ranks among the top institutions in the United States in terms of research output and quality in the life sciences. In 2004, the Times Higher Education Supplement ranked Salk as the world’s top biomedicine research institute, and in 2009 it was ranked number one globally by ScienceWatch in the neuroscience and behavior areas.

Dr. Brody is an accomplished scientist with more than 100 articles published in U.S. medical journals. He also holds two U.S. patents in the field of medical imaging. His many biomedical accomplishments include contributions in the fields of medical acoustics, computed tomography, digital radiography, and magnetic resonance imaging. He is a co-founder of three medical device companies, and served from 1984 to 1987 as president and CEO of Resonex Inc., a medical instrument manufacturer.

His contributions to the medical instrumentation field have led to Dr. Brody’s induction into several coveted organizations. He is a fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers (IEEE); the American Academy of Arts and Sciences; the American Institute of Biomedical Engineering; the International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine; the American Heart Association; the American College of Radiology; and the American College of Cardiology.

The Canadian Association of Radiologists recognized Dr. Brody’s contributions by making him an honorary member in 1974. He is also the recipient of the Outstanding Alumnus Award from UC-San Francisco’s department of Radiology; the American Heart Association’s Established Investigator Award; and the Western Thoracic Surgical Society Prize Manuscript Award.

A trustee of the Keck Foundation, an American charitable foundation supporting scientific, engineering and medical research in the United States, Dr. Brody is a national figure in efforts to encourage innovation and strengthen the U.S. economy through investments in research and education.

Dr. Brody serves as a member of the Scientific Management Review Board of the National Institutes of Health and on the board of directors of IBM and Novartis. He is a member of the Board of Trustees of Stanford University. He formerly served on the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, the Science Board of the Food and Drug Administration, on the Corporation of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and was a trustee of the Commonwealth Fund, the Whitaker Foundation and the Minnesota Orchestra.

A private pilot holding airline transport and flight instructor ratings, he has recently written and spoken extensively around the country to promote a fuller discussion of health care reform.

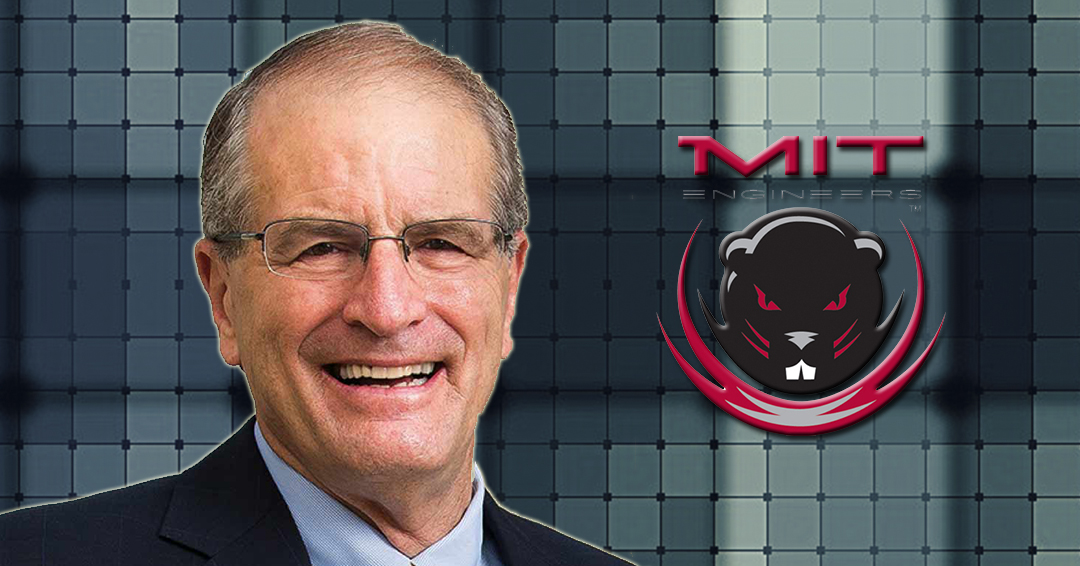

Inside Water: Water Polo, Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer & Chevrolet – The Life of Jam Handy

BRIDGEPORT, Pa. — The Collegiate Water Polo Association (CWPA) periodically likes to point out the connection of water polo to other areas of life – science, technology, pop culture, etc.

As May begins and the 2019 season begins to come to a close with the Women’s National Collegiate Club Championship this weekend and the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Championship in a week, and graduation ceremonies coming up around the country, it seemed appropriate to consider someone who most people do not know – although they have seen or been impacted by his work.

Born on March 6, 1886 in Philadelphia, Pa., Harrison James Handy acquired the nickname of “Jam”.

Don’t know who he is? Let us begin as Handy was an American Olympic breaststroke swimmer, water polo player and leader in the field of commercial audio and visual communications. A producer of training films, he is known for another production that helped launch the story of a deer with a nasal affliction.

Handy attended North Division High School in Chicago, and then the University of Michigan during the 1902–03 academic year. During his early life, Handy began swimming and introduced a number of new swimming strokes to Americans, such as the Australian crawl (regarded as the fastest of the four front primary strokes and now universally used during a freestyle swimming competition. This stroke gained additional popularity in the 1920’s thanks to Gertrude Ederle using it to cross the English Channel in 1926).

Now back to the story – Handy would often wake up early and devise new strokes to give him an edge over other swimmers. Swimming led to him getting a bronze in the 1904 Olympics at St. Louis, Missouri. Twenty years later he was part of the Illinois Athletic Club water polo team at the 1924 Olympics in Paris, France – a stretch of 20-years that established a new Olympic record for the longest period of time between first and last competition. Like his first appearance, Handy went home with a medal as the team won the bronze at that Olympics.

Some degree of luck – and a cartoon – would help direct his track in history as during his time at Michigan he was working as a campus correspondent for the Chicago Tribune when on May 8 he wrote an article about a lecture in the Elocution 2 class given by Prof. Thomas C. Trueblood.” Handy went on to describe how Trueblood had dropped to a bended knee in order to demonstrate how to make an effective marriage proposal – among other titillating elements of the lecture. John T. McCutcheon, a Chicago Record Herald cartoonist, followed the next day with a cartoon about a “Professor Foxy Truesport”.

Neither Trueblood nor university President James B. Angell were amused. Ten days after the initial article was published, Handy was suspended for a year for “publishing false and injurious statements affecting the character of the work of one of the Professors.” Handy was told he could re-apply one year later. Instead, Handy decided to apply to a different school, but he was unable to gain acceptance to other schools because of what had happened at the University of Michigan. Handy was accepted to the University of Pennsylvania, but was told to leave after two weeks of classes.

Tribune editor Medill McCormick tried to intervene on Handy’s behalf, but Angell refused to change the suspension. At that point McCormick offered Handy a job. Handy worked in a number of departments at the Tribune. It was during his time working on the advertising staff that Handy observed that informing and building up salespeople’s enthusiasm for the products they were selling helped to move more merchandise. He also began researching exactly what made people buy a particular product.

Handy left the Tribune to do further work on corporate communications. He worked with John H. Patterson of National Cash Register, who had used slides to help train workers. With help from another associate, Handy began making and distributing films that showed consumers how to operate everyday products. After World War I broke out, Handy began making films to show how to operate military equipment. During this time the Jam Handy Organization was formed.

The Jam Handy Organization was probably best known for producing the first animated version of the new Christmas story Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer directed by Max Fleischer. After the war, the Jam Handy Organization was contracted as the Chicago-Detroit branch of Bray Productions, creating films for the auto industry, Bray’s largest private client.

General Motors selected Handy’s organization to produce short training films as well as other training and promotional materials. One such film was Hired! – a training film for sales managers at Chevrolet dealerships.

Between 1936 and 1938, the Jam Handy Organization made a series of six animated fantasy sales films for Chevrolet featuring a gnome named Nicky Nome, which showed new Chevrolet automobiles saving the day from villains, often in retellings of classic tales such as Cinderella, the subject of two of those films, A Coach for Cinderella and A Ride for Cinderella. The other films were Nicky Rides Again, Peg-Leg Pedro, The Princess and the Pauper and One Bad Knight.

Handy also produced films for other companies and for schools. He’s estimated to have produced over 7,000 films for the armed services during World War II. Handy was noted for taking only a one-percent profit on the films, while he could have taken as much as seven percent. He was noted for never having a desk at work, instead using any available work space. Handy’s suits didn’t have pockets, as he thought they were a waste of time.

Handy was married to Helen Hoag Rogers and had five children. Despite his troubles with the University of Michigan, his son-in-law Max Mallon, granddaughter Susan Webb, and great-granddaughter Kathryn Tullis received degrees from the school. Handy also received an honorary doctorate from Eastern Michigan University.

Handy appeared swimming in a 1978 commercial asking for the public to support American athletes training for the 1980 Olympic games before the boycott. At the time of his filming he was the oldest living United States Olympic medalist.

He continued swimming on a regular basis until just a few days before his death on November 13, 1983 at the age of 97.

Inside Water: Water Polo Led Dr. Theodore Schlegel to the National Football League & Major League Baseball

BRIDGEPORT, Pa. — A 1983 graduate of Brown with a degree in Biological Sciences, Dr. Theodore Schlegel, M.D. helped the Bears capture the 1981 Collegiate Water Polo Association (CWPA) Championship and helped his alma mater make the 1979, 1981 and 1982 National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Championship tournaments.

As a freshman in 1979, he helped Brown earn a spot in the NCAA Championship hosted at the Belmont Plaza Pool in Long Beach, Calif. It marked the Bears’ second NCAA Championship appearance as the team fell to Stanford University (13-5 L) and Loyola University Chicago (11-10 L OT SD) before topping the United States Air Force Academy (15-10 W) to earn a Seventh Place finish.

After missing the 1980 NCAA Championship, Schlegel helped Brown claim the program’s inaugural league championship in 1981 to punch its ticket to the National Championship tournament back at the Belmont Plaza Pool. The Bears once again placed Seventh as the team fell to eventual National Champion Stanford (8-5 L) and the University of California-Santa Barbara (16-6 L) before again upending Air Force (9-8 W).

Arguably his best season came as a senior in 1982 as Brown finished second in the league title hunt, but claimed another trip to the NCAA Championship back at the Belmont Plaza Pool. The Bears placed Seventh for the third time during Schlegel’s tenure as the team fell to eventual National Champion the University of California-Irvine (13-2 L) and the University of Southern California (11-8 L) before stopping Loyola Chicago (7-5 W) – the team that prevented Brown from winning the 1982 league crown. For his efforts, Schlegel was named an Honorable Mention All-America selection by the ACWPC.

Following graduation from Brown, Schlegel attended the University of Cincinnati School of Medicine. A 1987 graduate of Cincinnati, he completed an internship in the Department of Surgery at the University of Utah Medical Center, a Residency in Orthopedic Surgary at Utah and a Fellowship at the Steadman Hawkins Clinic at the Vail Valley Medical Center.

A specialist in orthopedic surgery with specialization in disorders of the bones, joints and muscles dealing with knee and shoulder Injuries and disorders along with sprains and strains, he served as head team physician for the Denver Broncos of the National Football League (1994-2012), the associate team physician of Major League Baseball’s Colorado Rockies Baseball Club (1998-2012) along with serving as a consulting reviewer for the American Journal of Sports Medicine, the Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery and the Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine.

For his work with the Broncos, including serving as team physician during the club’s 1997 and 1998 Super Bowl Championship seasons, Schlegel was presented the 2012 Jerry “Hawk” Rhea Award as the Outstanding NFL Team Physician per the Professional Football Athletic Trainers Society (PFATS).

The co-founder of the Steadman Hawkins Clinic in Denver, he currently serves as an Associate Professor in Orthopedics at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.