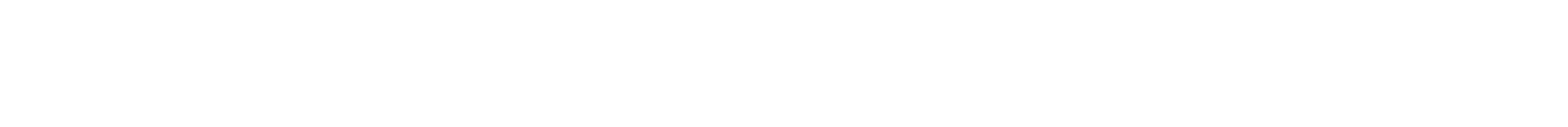

BRIDGEPORT, Pa. — A former Syracuse University water polo player, Sheldon Leonard is arguably the most influential individual upon the medium of television in the history of the device.

Born Sheldon Leonard Bershad in New York City on February 22, 1907 to middle class Jewish parents Anna and Frank Bershad, the Museum of Broadcast Communications notes that for “nearly two decades, from the early 1950s through the late 1960s, Sheldon Leonard was one of Hollywood’s most successful hyphenates, producing–and often directing and writing–a distinctive array of situation comedies, of which three justly can be considered classics (The Danny Thomas Show, The Andy Griffith Show, The Dick Van Dyke Show). Although he assayed the hour-long espionage form with conspicuous success as well, the sitcoms remain the Leonard hallmark. Long before Taxi and Cheers, Leonard was overseeing the creation of literate, character-driven ensemble comedies that blended the domestic arena with the extended families of the modern workplace.”

Following his formative years in Belleville and later lower Manhattan, he attended Stuyvesant High School and was the right guard on the 1925 Municipal Championship football team, and advanced on to Syracuse University where he studied theater and was a varsity athlete on the swimming/diving and water polo teams.

Following graduation, he moved into the role of head counselor of Camp Wakitan in the Ramapo Mountains of upstate New York before planning a career as a stockbroker on Wall Street.

History has a funny way of changing plans, however, as his first day as a junior broker for Bauerdorf and Company occurred on October 24, 1929. On that date, the market shed 33 points – a drop of 9 percent- to begin the Great Stock Market Crash of 1929 with the subsequent impact of the Great Depression occurring for the next 12 years to the beginning of World War II.

Out of work two weeks after beginning his new job, Leonard worked odd jobs until being tipped off to the Paramount Theatre Company’s program for assistant theatre managers. Following completion of the course, he was sent to the Eastman Theatre in Rochester, New York – a fortuitous event which launched his stage and screen (both big and little) careers.

Following a few years working behind the scenes, he took a position on the stage in the early 1930’s. After six years acting on Broadway–during which time he also took his first stab at directing, for road companies and summer theater–in 1939 Leonard made the move to Hollywood, where he would go on to appear in fifty-seven features over the next fourteen years including notable cinematic events as to Have and Have Not, It’s a Wonderful Life, Another Thin Man, Decoy, Abbott and Costello Meet the Invisible Man, Sinbad the Sailor, Guys and Dolls and Pocketful of Miracles (with Frank Sinatra).

Besides his cinematic appearances, he was keeping busy on the radio with regular roles on several programs (The Jack Benny Show, The Lineup and Duffy’s Tavern, to name only a few), and guest parts on dozens of others. Although Leonard played a number of roles on both the silver screen and radio, he is best remembered for his incarnations of quietly-menacing gangsters due to his Brooklyn-toned voice.

One of his most notable roles was portraying an eccentric racetrack fan known as the “Tout” on The Jack Benny Program in the late 1940’s and early 50’s. His role was to salute Benny in different locations with the same quote “hey Bud, come here a minute”, ask what Benny was going to do, try to argue him out of that course of action using irrelevant racing logic. He also appeared on “The Adventures of the Saint”, most often playing thugs or gangsters, but sometimes in more positive roles.

As the 1940’s wore on, he kept acting and took up writing for radio programs selling scripts for anthology shows, all of which he retained the rights to for future potential sales. In addition, he tried his hand at directing while learning the inner workings of the writing and producing fields.

After a while, the advent of television brought about a new slew of opportunities as he turned to writing for the new media outlet.

Moving away from radio, Leonard signed on as director of the Danny Thomas series Make Room for Daddy in 1953. He was promoted to producer in the show’s third year, remaining its resident producer-director for six more seasons. Between 1954 and 1957 he also found time to produce and direct the pilot and early episodes of Lassie and The Real McCoys (which was produced by Thomas’ company), write and direct installments of Damon Runyon Theatre – as well as act in a 1954 summer replacement series, The Duke. In 1961 Leonard became Executive Producer of the Thomas series (titled The Danny Thomas Show), at which time he and the comedian teamed up to form their own production firm.

T and L Productions would go on to make a lasting mark on television comedy. At its peak in 1963, T and L had four situation comedies in prime time, with Leonard serving as Executive Producer on all four: The Danny Thomas Show, The Dick Van Dyke Show, The Andy Griffith Show, and The Bill Dana Show. Through their own separate companies Leonard and Thomas also owned an interest in a fifth sitcom, The Joey Bishop Show, although Leonard had no creative role in the series after directing the pilot. To complete the T and L comedy empire, the partners each owned an interest in My Favorite Martian by virtue of Thomas’ financing and Leonard’s direction of the pilot, and also owned The Real McCoys syndication package. Although the Bishop and Dana programs were short-lived, Danny Thomas, Dick Van Dyke, and Andy Griffith were all certifiable Top Ten Nielsen hits.

Consider some of the characters and actors which were on these shows. Most notably, consider The Andy Griffith Show launched the career of not only Griffith, but also Don Knotts and actor/director Ron Howard.

Further, it was Leonard who recognized the story and character quality in a failed pilot written by and starring Carl Reiner, and resurrected it by casting Dick Van Dyke in the lead role–retaining Reiner’s writing talents – for The Dick Van Dyke Show.

Behind the scenes, his impact was equally felt as he fostered and mentored the talent of writers, notably Danny Arnold (Barney Miller), and the teams of Garry Marshall and Jerry Belson (The Odd Couple, Happy Days, etc.), and Bill Persky and Sam Denoff (That Girl, Kate and Allie).

Although not the first to come-up with the idea of a spin-off (radio program Fibber McGee & Molly spun-off the Great Gildersleeve in the 1940’s), Leonard brought the idea to television to avoid the cost of making a pilot episode.

Both the Andy Griffith and Joey Bishop shows began with “back-door pilots” (directed by Leonard) aired as episodes of Danny Thomas; similarly, Bill Dana’s “José Jimenez” character began as a recurring character on the Thomas show before setting out on his own series. While the Dana and Bishop programs did not work out so well, another spinoff from The Andy Griffith Show did in 1964 when sent a popular resident of Mayberry off into six years of military misadventures on Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C.

Following the break-up of his partnership with Thomas in 1965, Leonard kept working and came up with the comedic spy series I Spy.

However, the most significant aspect of the series was Leonard’s decision to cast then not-widely known African-American comedian Bill Cosby opposite Robert Culp as the series leads to make Cosby the first African-American lead actor in network television history. The series was nominated for Outstanding Dramatic Series Emmy every year of its three-year run, earned Leonard an Emmy nomination for directing in 1965 and launched the career of actor Bernie Koppell, who went on to play Doc on Love Boat.

In addition to directing and producing, he continued to work as an actor recreating his radio role as the racetrack tout on Jack Benny, appearing as Danny Williams’ agent on Danny Thomas, and doing a gangster turn in a Dick Van Dyke episode. Still typecast after almost forty years, Leonard acted the tough guy yet again in 1975 as the star of the short-lived series Big Eddie (as a gambler-turned-sports arena owner), and once more in 1978 in the made-for-TV movie The Islander (as a mobster). That same year Leonard acted in the TV movie Top Secret, a tale of international espionage starring and co-produced by Bill Cosby. More recently, Cosby recruited Leonard to fill the Executive Producer slot on I Spy Returns, a 1993 TV-movie sequel that reunited Culp and Cosby as the secret agents.

He was also active in cartoons and adverting serving as the voice of lazy cat Dodsworth in two 1950’s Warner Bros. cartoons before providing the voice of Linus the Lionhearted in a series of Post Crispy Critters cereal commercials in 1963-64. He repeated his performance as Linus in a Saturday morning cartoon series which ran on CBS (1964-66) and ABC (1967-69). In addition, he shares the title of being the first Miller Lite spokesman with crime author Mickey Spillane.

In one of his final acting roles, he made an appearance on potentially the pinnacle series of the 1980-90 period, Cheers, on which he appeared as the proprietor of “The Hungry Heifer,” Norm Peterson’s favorite eating establishment.

The recipient of multiple awards, including three Emmys and a Golden Globe, he was honored by the NAACP for his role in breaking the “color barrier” with Cosby’s casting on I Spy and was inducted into the Television Hall of Fame in 1992. Even today, he continues to receive homages as the lead characters on the CBS Emmy-nominated show “The Big Bang Theory” are named Sheldon and Leonard in his honor.

Active on screen and in television production until his death on January 19, 1997 in Culver City, California at the age of 89, his position of success and impact on American culture following a time as a collegiate athlete was recognized by the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) in 1969 as he was the recipient of a Performing Arts Salute, one of only five water polo athletes recognized by the organization with a post-collegiate award/salute.

Actor, director, producer, innovator, water polo player. Not a bad career, and one that deserved a spotlight.

Thanks to the Museum of Broadcast Communications for assistance in this piece and Sheldon Leonard’s autobiography “And the Show Goes On”. Originally published in 2009.