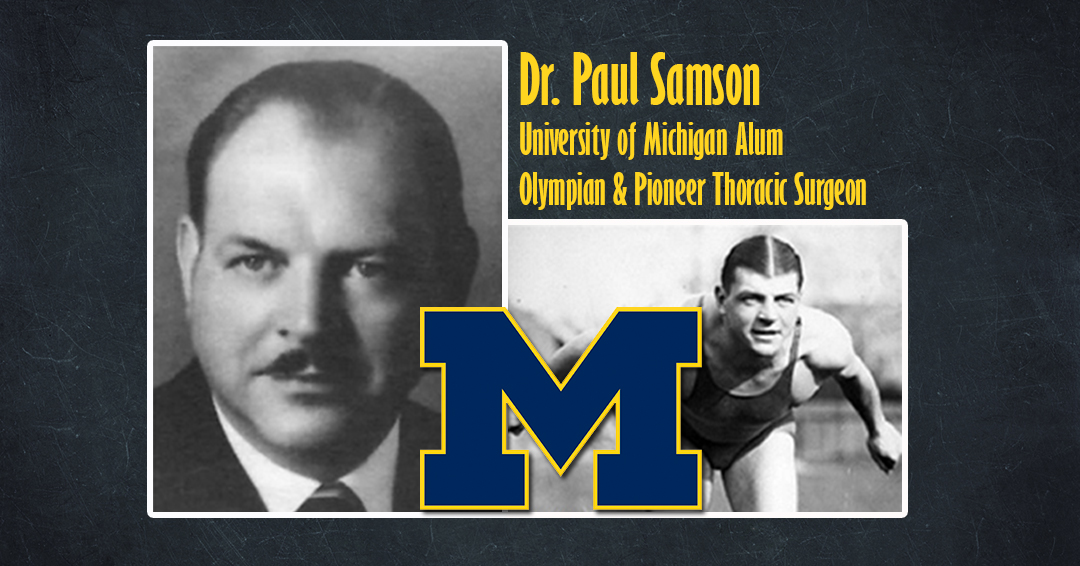

BRIDGEPORT, Pa. — In the continuation of the Collegiate Water Polo Association (CWPA) look back at alumni of member institutions who made a mark at the Olympic games, the league recalls University of Michigan alumnus and pioneering thoracic surgeon Paul Curkeet Samson.

Born on June 12, 1905 in Emporia, Kansas, Samson represented the United States in both swimming and water polo at the 1928 Summer Olympics in Amsterdam, Netherlands. Samson swam for the Gold Medal winning United States team in the qualifying heats of the men’s 4X200-meter freestyle relay, establishing a world record time of 9:38.8. Because he did not swim in the relay event final (which set another new world record of 9:36.2 with the team of future 1932 water polo Olympian Austin Clapp, Walter Laufer, George Kojac and Johnny Weismuller), Samson was not eligible to receive a medal under the 1928 Olympic rules. When not swimming, he was also a member of the fourth-place U.S. water polo team with Fordham University alumnus Joseph Farley and future Tarzan actor Weismuller.

The United States is recorded as having played three games during the tournament – a 5-0 quarterfinal loss to Hungary followed by consolation games versus France (2-1 L) and Malta (10-0 W). Overall, the event consisted primarily of a single-elimination bracket that determined the gold and silver medals. The bronze medal was supposed to be awarded through a modified Bergvall system tournament, in which the teams who lost to the top two nations (that is, Belgium and Great Britain—who had lost to Germany—and France, the United States, and Argentina—who had lost to Hungary) would conduct another single-elimination tournament for the third place. However, the tournament organizers did not understand the system. The Official Report of the Olympic Games lists three third-place matches, in which France defeated Great Britain, the United States, and Argentina in succession. To additional matches of the United States-versus-Malta and the Netherlands versus Belgium are also listed. However, it is noted that, “some of the matches played may have been friendlies or exhibitions.” The France–Great Britain match was treated as the bronze medal game.

Prior to his time on the Olympic stage, Samson competed in swimming at the University of Michigan. In 1927, he won the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) national championships in both the 220-yard freestyle (2:26.6) and the 440-yard freestyle (5:28.7). In addition, he competed for the Illinois Athletic Club in swimming. Further, he was part of a pair of national championship water polo teams at Michigan (the NCAA Championship did not begin until the 1960’s).

At 6 feet-6 inches tall, Samson acquired the nickname ‘‘Buck’’ – a name he would use for the remainder of his life – not only for his formidable stature but also for his physical prowess and competitiveness. His competitive nature spread to the classroom where he was recipient of the Big Ten Conference Medal of Honor in 1927 for excellence in scholarship and athletics

A 1928 graduate of Michigan with a Bachelor of Science in Medicine and a Doctorate of Medicine cum laude (completing both programs while training for swimming and water polo at Michigan and preparing for the Olympic games), Samson completed general surgical residency at Northwestern University, receiving his Master of Science in Surgery in 1935. He continued his surgical training at the University of Michigan as one of the trainees in the first thoracic residency program.

He moved West in 1937 to begin a surgical practice in Oakland, California. He joined the staff of several hospitals and sanitariums for tuberculosis in northern California and served in the Army Reserve Medical Corps from 1931 to 1941. With involvement of the United States in World War II in December 1941, Samson joined the Second Auxillary Surgical Group and was deployed in the Mediterranean and European theaters. Along with treating traumatic injuries, he gained the distinction of performing what was probably the first successful pneumonectomy (partial or total removal of a lung) in the overseas theater using the individual ligation technique.

Although there was minimal improvement in thoracic surgery between World War I and World War II, restoring cardiac and pulmonary function had not been widely appreciated and evaluated. To correct this, Samson, along with fellow surgeons Lyman Brewer and Thomas H. Burford, persuaded the surgeons at Army headquarters to set up a thoracic surgery center on a trial basis. In July 1943, the first such chest center in the Army Medical Corps was established in Bizerte, Tunisia. To overcome the official skepticism of the leadership about a thoracic surgery unit, Samson, Brewer and Burford demonstrated that well-trained thoracic surgeons could substantively lower the mortality rates of chest wounds.

After the conclusion of World War II, Samson retired from active service as a lieutenant colonel in January 1946. He received numerous commendations for his military service, including the Bronze Arrowhead for D-Day landing in southern France in 1944, the Legion of Merit (Mediterranean theater of operations, 1945), Bronze Service Stars for seven campaigns and three service medals.

Samson returned to northern California to continue his thoracic surgery practice, specializing in the treatment of tuberculosis and empyema. In 1946, Samson was one of the first surgeons in the West to limit his scope of practice to thoracic surgery and was considered the 22nd ‘‘pure’’ thoracic surgeon in the country. That same year and until 1958, Samson started and directed the thoracic surgery training program at Highland General Hospital in Oakland, which was the first approved training service in thoracic surgery north of Los Angeles on the West Coast. Samson’s surgical expertise was widely recognized and helped train Stanford residents and had an appointment at Stanford University, eventually retiring as clinical professor of surgery.

Samson recognized the need to document the surgical lessons that he and his colleagues gained from the war,and, later in practice, he emphasized to his trainees the importance of clinical and experimental research in thoracic surgery. He authored over 130 scientific contributions ranging from complications of tuberculosis and other chest infections, pulmonary and mediastinal tumors, esophageal disorders and aortic coarctation, including over 20 publications on thoracic trauma during the war and in civilian life.

A man who earned a level of acclaim from his swimming exploits – and friendship with Weismuller – Samson was well known for his joie de vivre and appreciation for a good time. During World War II, to honor his friend Victor Bergeron, Jr. – who founded a chain of Polynesian-themed restaurants that bore his nickname, “Trader Vic”, and claimed to have invented the Mai Tai – Samson and his Army buddies started the first branch in the Italian theater, similar in functionality and production of the “Swamp” bar in the popular “M.A.S.H.”television program.’’

To honor him for his service to thoracic surgery, Samson’s close friends and colleagues founded the Samson Thoracic Surgical Society of Western North America in 1974 because they believed that such an honor was due him during his lifetime. Following his death on February 10, 1982 at the age of 76, the Samson Thoracic Surgical Society was renamed The Western Thoracic Surgical Association in 1983 to achieve representation at the American College of Surgeons Board of Governors, which did not recognize societies named after an individual. Samson’s name, however, is preserved in the Samson Endowment Fund, the Samson prize for the best resident paper, and other activities of The Western Thoracic Surgical Association.