BRIDGEPORT, Pa. — Due to the death of United States Supreme Court Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, many things will be written about her legal career. What will likely not appear in the press is that fact that Ginsburg credited a water polo player with helping to launch the diminutive attorney on the path to the nation’s highest court.

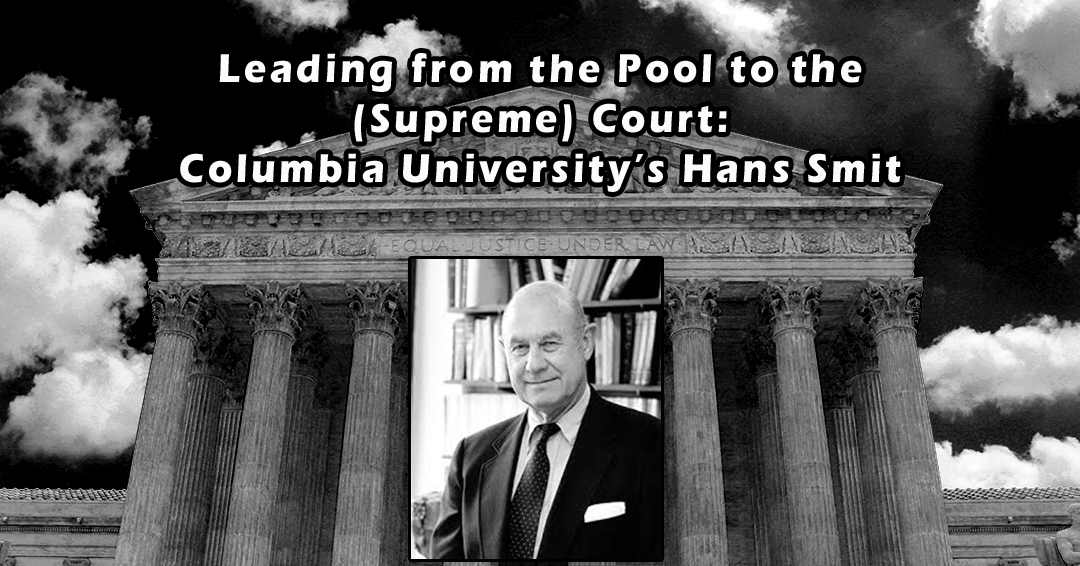

A water polo player in his native Amsterdam and later with the New York Athletic Club, Hans Smit ’58 LL.B. was a distinguished Columbia University Law School professor and a leading scholar and practitioner in the fields of international arbitration and international procedure. He passed away on January 7, 2012, at the age of 84.

Smit was born on August 13, 1927, in Amsterdam, Netherlands. He told colleagues that his mother wanted him to become a doctor but that he eschewed the University of Amsterdam’s faculty of medicine in favor of the law faculty in part because law classes started later in the day.

After earning his LL.B. and LL.M. from the University of Amsterdam in 1946 and 1949, respectively, Smit went back and forth between private practice in The Hague and New York City, and he received a Fulbright scholarship in 1953. He earned a master’s degree at Columbia in that same year and graduated first in his class with an LL.B. from Columbia Law School in 1958. After graduation, Smit worked for two years at Sullivan & Cromwell in New York City. It was Smit’s wife, Beverly, who persuaded him to try his hand at being a law professor, he said.

Smit joined the Columbia Law School faculty in 1960, assuming directorship of the Project on International Procedure, which attracted top legal minds, including 1959 Columbia graduate Ginsburg, who served as a research associate and associate director. Under Smit’s leadership, the program prepared a revised version of Section 1782 of Title 28 of the United States Code, which Congress enacted in 1964. Smit’s team drafted the revision together with the U.S. Commission and Advisory Committee on International Rules of Judicial Procedure, for which Smit served as a reporter for a decade.

The impact of the 1964 revision was seismic, Smit noted in a 1998 law journal article. “[It] greatly liberalized assistance given to foreign and international litigants and tribunals and, in the thirty-five years that followed its enactment, has been applied in scores of cases,” he wrote in the Syracuse Journal of International Law and Commerce.

In 1963, Smit founded the Columbia-Leiden-Amsterdam Summer Program, which gives law students and practicing lawyers from around the world the opportunity to travel to the Netherlands for one month of intensive training in American law. Smit recalled in 2008 that the idea for the program, which continues to this day, emerged from his experience teaching in U.S. and Dutch classrooms.

“The American focus on fact-specific situations, and the challenge to probe the questions and provide appropriate answers was totally different from the memorization I experienced in my European studies,” Smit said. “So when I was appointed to the Columbia Law faculty, I said, ‘We should really expose the Europeans to American lawyering.’”

Smit, who led the program until 1988, said it became a powerful recruiting tool for Columbia Law School. “It . . . gave us a real advantage,” Smit said in 2008. “As far as Europeans were concerned, we were the international law school. We became the natural attraction point for people who wanted to study in the United States.”

Smit was also a driving force behind the creation of the J.D./Master in French Law Program, offered jointly by Columbia Law School and the University of Paris 1 – Panthéon-Sorbonne. Those who complete the four-year program receive law degrees from both schools and qualify for admission to bar examinations and the bar in both France and the United States.

In 1965, Smit further helped burnish the Law School’s reputation as a global hub for the study of international law as director of the Project on European Legal Institutions, which was organized with a grant from the Ford Foundation. The project yielded a comprehensive work, The Law of the European Economic Community, which Smit co-edited with Peter E. Herzog. The book was the first multi-volume, article-by-article treatise on the subject in the English language, and it was subsequently reprinted under the title The Law of the European Union.

Smit also served as director of the Parker School of Foreign and Comparative Law at Columbia Law School from 1980 to 1998, of the Center for International Arbitration and Litigation Law from 1997 to 2005, and of the Center for East European Law from 1998 until 2005. He also authored and edited the World Arbitration Reporter, a multi-volume work on arbitration laws throughout the world.

A reporter to the U.S. Commission on International Rules of Judicial Procedure from 1960 to 1969, Smit served as an adviser to the U.S. delegation to the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law and as a consultant to the Judicial Conference of the State of New York. In 1978 he was appointed to the Stanley H. Fuld Chair at Columbia Law School.

Smit had a reputation as an exacting teacher who inspired both anxiety and adoration in his students, many of whom say their appreciation of his tutelage only increased after graduation.

Smit published numerous books and articles on civil procedure and international arbitration, litigation, and business transactions. He also wrote influential amicus briefs for U.S. Supreme Court cases, including Orr v. Orr, in which the Court struck down as unconstitutional an Alabama statute that barred men from receiving alimony payments.

Smit was a member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences and the International Academy of Comparative Law. In 1987 he was made a Knight of the Order of the Netherlands Lion by Queen Beatrix.

Outside of the legal world, Smit was keenly interested in the Middle Ages and collected 14th- and 15th-century art and furniture. He was also an accomplished water polo player. He said he missed an Olympic spot with the Dutch national water polo team only because of a dispute with the coach, who suspended him for gambling instead of resting in the hotel during the 1947 European Championship in Monte Carlo. “In the middle of the day—it was absolutely ludicrous!” Smit told the New York Daily News in the early 1980s. “I told him I would get all nervous and sweaty trying to rest. Gambling was far more relaxing.”

He continued playing until his final days noting to the Daily News, “Water polo balances my life,” he told the Daily News.

Upon Smit’s death in 2012, Ginsburg issued the following message:

“Among people who have encouraged and aided me in my life in the law, Hans Smit merits top billing. My fondness for Hans dates from our first encounter in 1961, when he invited me to lunch at the Harvard Club and asked: “Ruth, how would you like to co-author a book about Civil Procedure in Sweden?” It was an idea that never occurred to me. But Hans described the work in his typically enthusiastic, utterly persuasive way. He also proposed that I assist him and his No. 1 aide, Arthur Miller, in developing other ventures of Columbia’s Project on International Procedure, a multi-faceted endeavor launched and superintended by Hans.

In those days I was rather shy. Hans was the ideal person to help me overcome that trait. With contagious confidence, he encouraged me to speak in public, to write for law journals, even to take over his civil procedure class for a week. He was my rabbi in 1971, when Columbia at last decided a tenured woman belonged on the faculty.

Hans brought me into the comparative law circuit starting in the early 1960s, influencing my perspective on legal issues ever after, and advancing my appreciation of fine food and vintage wine. On the pleasures of fine dining and wine, I hasten to add, my husband, Chef Supreme Marty, was by far the better colleague for Hans.

In 1978, when Hans and Beverly’s building caught fire, they stayed at our apartment for some months while Marty and I were spending a semester at Stanford. Hans read some of Marty’s reprints left on a dining room shelf, and decided Marty was just the person Columbia needed to enhance its tax faculty. With irresistible encouragement and support from Hans, Marty left 21 years of law practice in New York to begin a law teaching career from which he derived great satisfaction. True, Marty did not stay at Columbia very long. President Jimmy Carter offered me a good job in Washington, D.C., the next year, 1980, and Marty transferred from Columbia’s faculty to Georgetown’s.

That was not the end of Hans’ sponsorship of professors Ginsburg. When daughter Jane decided, in the late 1980s, on a law teaching life, Hans was again the leading promoter. He forecast not only Jane’s promise as a teacher, but the growth potential of the field she had chosen—literary and artistic property law.

Hans, all who have experienced him as teacher, colleague, writer, or bon vivant know, is a man of many talents—fluent in several languages, legendary water polo champion, skilled arbitrator, bargainer, collector of fine art, astute real estate investor, and remarkable buildings and homes renovator. He is truly a man of the world, like Odysseus, a man never at a loss. I count it my great good fortune that for more than 50 years he has been my counselor and treasured friend.”